This post originally appeared on Arizona State University’s ASU Now site on August 26, 2019.

The trial of Scott Warren took center stage this summer in the nation’s passionate debate over immigration. Warren, a humanitarian aid worker with the group “No More Deaths,” was facing felony charges — and up to 20 years in prison — for aiding immigrants in the southern Arizona community of Ajo. That assistance included providing water and other basic assistance and, according to the federal authorities, helping them avoid detection. To government prosecutors, he was a felon aiding and abetting in illegal immigration. To his defenders, he was simply a compassionate Samaritan following a moral calling to help those in desperate need.

But despite the national spotlight and intense media scrutiny, little was known about the investigation that had led to Warren being charged in the first place. A journalist with The Intercept had hit a roadblock trying to gain access to sealed court documents, and on June 11, jurors were unable to agree on a verdict and the case ended in a mistrial. For the First Amendment Clinic at the Sandra Day O’Connor College of Law at Arizona State University, it was the perfect case.

Answering the call

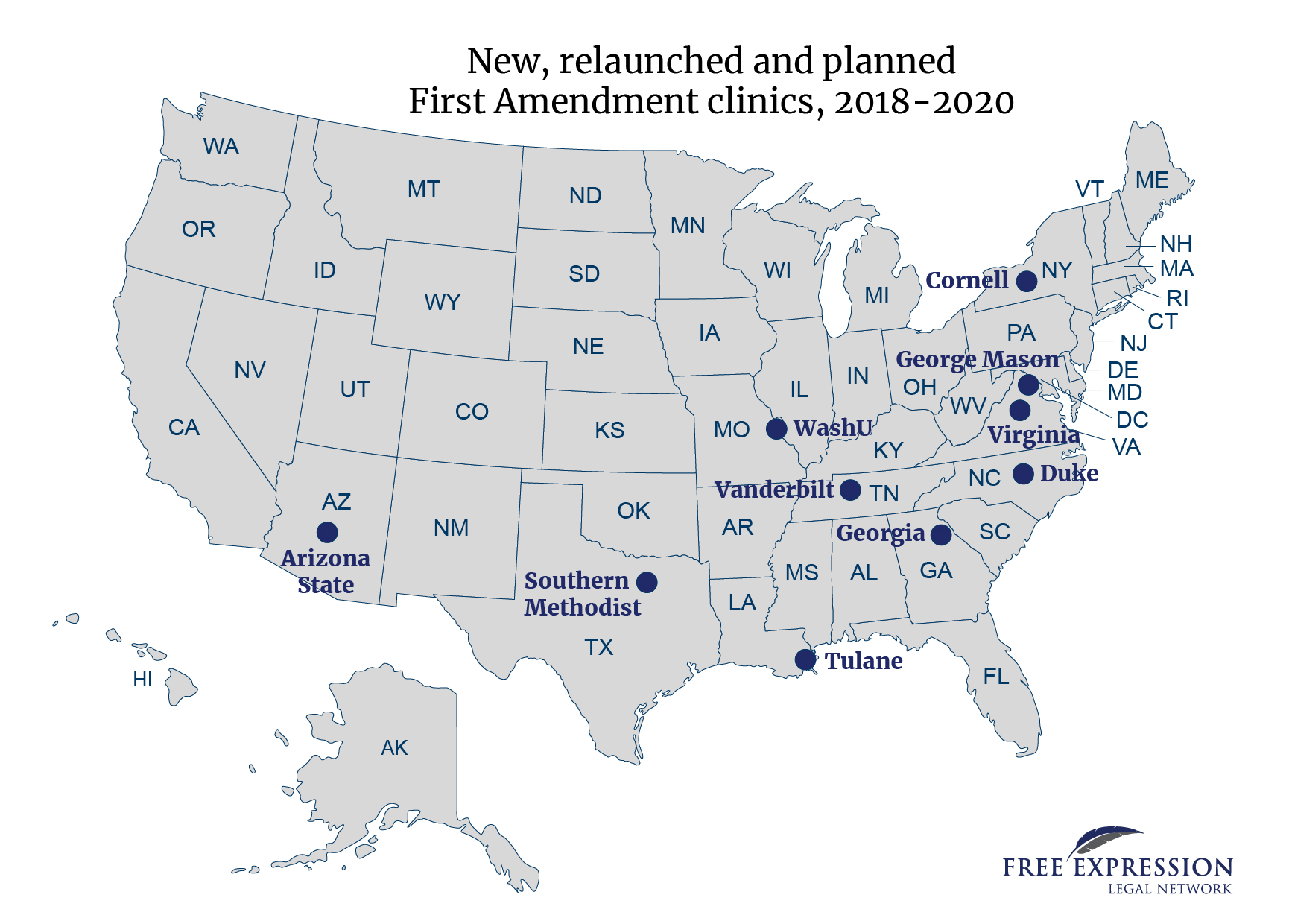

The clinic was launched in fall 2018 with the mission of helping to protect and advance freedom of the press and train future lawyers on First Amendment issues. When Executive Director Gregg Leslie received the call for help from a longtime associate at The Intercept, there was no hesitation.

“It was the perfect opportunity for us, so we jumped at the chance,” said Leslie, himself a former journalist.

The case was not only unfolding in Arizona, in federal court in Tucson, but Warren had been a faculty associate in ASU’s School of Geographical Sciences and Urban Planning. Faculty associates are hired on a course-by-course basis.

The work began, with neither the clinic nor The Intercept knowing exactly what they might uncover.

“When we talked about these documents, all we knew is that something was attached to a motion to dismiss, and that it involved conversations, probably, among Border Patrol agents,” Leslie said, adding that when somebody is prosecuted for a crime in federal court, there should be little to no secrecy surrounding the details of the investigation.

“There were allegations that the Border Patrol was trying to go after somebody because he was providing water and other assistance to people who might otherwise die as they were crossing a desert,” Leslie said, underscoring the passion that surrounded the case. “And, of course, the point other people would make is that that crossing into the U.S. without documentation is itself illegal, and that’s why the government is going after them. But Scott Warren had this fundamental belief that he could not stand by and watch people die in the desert. So if he was being targeted for that belief, and he was being prosecuted, it was important to know exactly what the Border Patrol did and didn’t do leading up to the arrest.”

The trial was approaching when the summer semester began. Ryan Bailey, one of the clinic’s summer students, would soon be playing a key role.

Students can be provisionally licensed to argue in state court if they’ve taken two semesters of law school. But an extra semester is required for federal cases. Ryan was the only student who fit that criteria.

Other students worked with Bailey on the briefing and all the research that went into it, but if they were granted oral argument on the motion to unseal the documents, he would have to be the one to argue before U.S. District Judge Raner Collins.

Bailey welcomed the challenge.

“I hadn’t taken a First Amendment class, so I was learning and having to apply what I was learning at the same time,” he said. “Thank goodness for Professor Leslie, though. He’s amazing and can always answer any question.”

The argument to unseal

In federal criminal cases, the Brady Rule and the Jencks Act govern most discovery issues. Under the Brady Rule, prosecutors are required to turn over potentially exonerating evidence to the defense at trial. And the Jencks Act covers incriminating evidence, requiring that prosecutors turn over verbatim statements or reports made by witnesses — but that is only required to be turned over after the witnesses have testified.

To speed things up, evidence is often shared in advance, as was the case in the Warren trial. And at the prosecution’s insistence, the two sides entered into a nondisclosure agreement to keep that evidence sealed; otherwise, the prosecution was going to be less forthcoming with disclosures.

But as Leslie points out, the First Amendment guarantees the public the right to access the information, and the government must provide a compelling reason to seal such documents. A nondisclosure agreement doesn’t supersede the public’s First Amendment rights. But it’s not uncommon for attorneys, and sometimes judges, to be mistaken on the issue.

“That comes up in a lot of cases in a slightly less formal context where a party will turn over this material to the other party and expect it to be kept confidential, and they incorrectly assume the right to confidentiality” Leslie said, noting that magistrate judges, not Collins, had been involved in the initial decision to seal the documents. “So in that sense, it wasn’t that surprising that the prosecution in this case made that argument. But it’s problematic.”

Leslie says every case is different, so there’s no textbook approach for the clinic’s students to follow.

“You have to do research, begin to formulate your arguments, then do more research and build a strategy as you go,” he said. “There is no real lesson plan to follow in a clinical case like this.”

Oral arguments were made before Collins on July 9. Bailey had been in a federal courtroom before, as an extern for U.S. Magistrate Judge Deborah Fine, but never in a situation like this.

“Normally when you’re in federal court, there’s a couple of people on defense, a couple people on the plaintiff side, some of the court people, and that’s it,” he said. “But for this, it was a pretty full courtroom. I knew my argument backward and forward and I knew the cases, but still, it was a little bit nerve-wracking.”

The prosecution’s argument was simple: The two sides had entered into a nondisclosure agreement, so the documents should remain sealed. Bailey countered that without a compelling reason to keep those documents sealed, the two sides did not have the right to strike an agreement to keep that information from the public.

Bailey thought he was on solid legal ground and that the prosecution had not made much of a counter-argument.

“I was pretty confident,” he said. “You never know how things will go, but I was confident that we were on the right side of the argument.”

Collins made his ruling three days later, on July 12, agreeing with Bailey that the government’s request to maintain the nondisclosure agreement could not be reconciled with the public’s right to know.

It was a big win for the media, as the Arizona Republic, the New York Times, the Washington Post, CNN and the Associated Press had also signed on as clients of the clinic in the pursuit of the sealed documents. And it was a big win for the First Amendment Clinic and Bailey, the third-year law student practicing with a provisional license.

“It was pretty amazing,” Bailey said. “I was smiling ear to ear. I called my parents. I don’t think these opportunities happen very often for law students, especially in federal court.”

The documents were made public on July 19, outlining the more than eight-month investigation that led to Warren’s arrest. The Intercept and other media outlets published detailed accounts of the investigation, allowing the public to see how and why Warren was arrested, and how the federal government allocated its resources.

And that, Leslie says, demonstrates how critical public access is to a free and democratic society.

“We’re talking about an incredible power of the law enforcement apparatus, with the courts able to deprive people of their liberty,” he said. “And they’re doing it in the name of the people. So if that’s happening, it’s essential that anything that the government relies on in depriving someone of their liberty be public so that we know exactly how the government is acting in our name.”

And if there is no oversight or accountability, he said, corruption will follow.

“We just know that,” he said. “We know that from how human institutions work. Special interests will be favored or certain interests will be favored over others, and we won’t get to know about it. So you really need constant public oversight, to keep the government accountable. And that’s essentially what these cases are about.”

Thankful to be at ASU Law

For Bailey, it was the latest twist in an academic journey that initially took him to Arizona Summit, a downtown Phoenix law school that lost its accreditation with the American Bar Association in July 2018 and closed shortly thereafter. Upon transferring to ASU Law, he was astounded by the contrast.

“It’s beyond comparison,” he said. “Just so many more opportunities. Especially opportunities like this, the First Amendment clinic and the externships. You learn about the law in the classroom, but you need to learn how to apply it as well. And without those kinds of opportunities, you’re really not prepared to be an attorney.”

Leslie said that in addition to giving students like Bailey the knowledge and experience to be successful, the clinic has an expansive mission to protect all elements of the First Amendment.

“We want to be involved in anything affecting the First Amendment, whether it’s this kind of public accountability, through open-records requests, defending libel cases or defending protesters,” he said. “It’s a broad mandate, but it essentially all comes down to the fact that we want people to feel free to exercise their First Amendment rights.”

Bailey said he can’t recommend ASU Law, or the First Amendment Clinic, highly enough.

“ASU Law is one of the best programs in the country,” he said. “The professors are very knowledgeable, and you’re surrounded by smart students who challenge you. So you just learn more in that environment. And as far as the First Amendment Clinic, I was able to get a comprehensive experience, with all the research, writing and talking to clients. I never imagined that I’d be arguing something in federal court.”